In this week’s episode of Bustles and Broadswords, another one from the 2021 archives to commemorate the 100th anniversary of women fencing being allowed to compete in the Olympic Games!

While Toupie Lowther did not compete in that momentous 1924 edition of the Olympic Games, she still made history as a woman fencer opting to wear trousers, establishing her lesbian gender non-conforming self on the sport…before going on to lead an all-women ambulance driving unit in WWI. Oh, and before being the probable source of inspiration for the first lesbian novel! Yes, that’s all.

Transcript

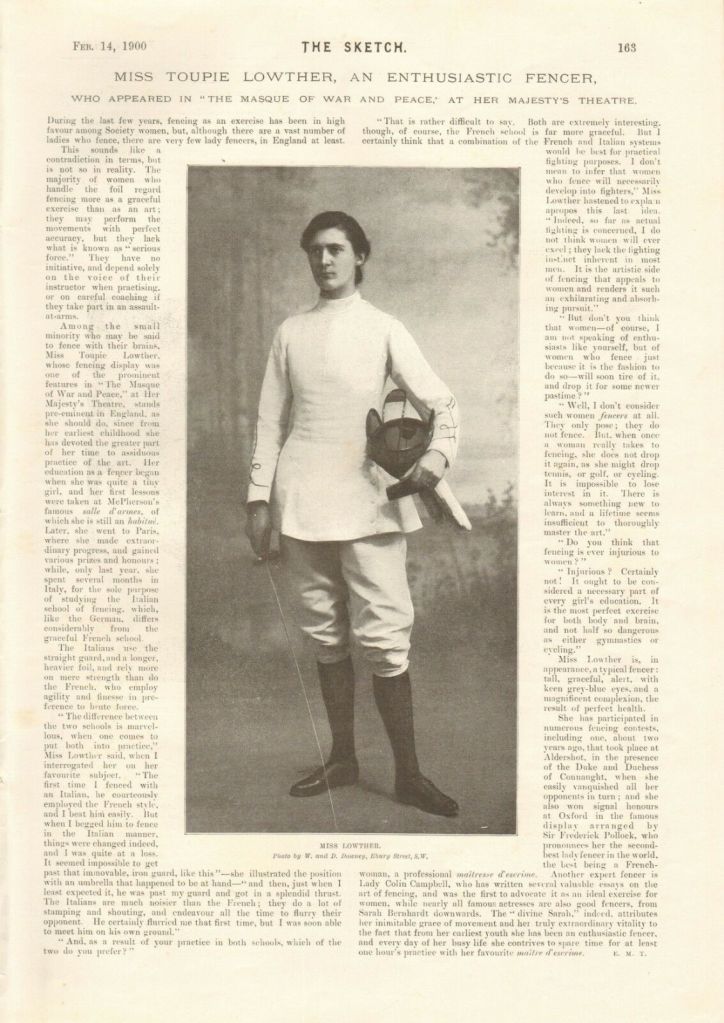

Hi and welcome to Bustles and Broadswords where I tell you all about women with swords throughout history. I’m Claire, a curator, art historian and fencer. Also a massive lesbian who likes finding other women loving women…not just on dating apps but you know – in history! But sometimes – they find me. And no this isn’t a lesbian ghost haunting situation. One night I was casually looking up fencing uniforms for women from the early 20th century (I mean – what ELSE am I supposed to do with my free time?) when suddenly I see her. Staring at me from a 1900 newspaper cutting in a pair of fetching fencing breeches. My historical gaydar pings. As I do more research it’s blaring full steam ahead. I have just found a lesbian fencer from the early 1900s and I wasn’t even trying.It’s 1898, at the Military Gymnasium of the Army Camp…in Aldershot. I have no idea where that is. But it’s presumably somewhere in the United Kingdom. This headstrong woman makes her way onto the fencing piste. She’s tall, dark hair scraped back into a bun, with a determined, steely gaze. The weightlifting she does alongside her tennis-playing make her a commanding presence with killer arms. She strides along to her competition for her first salute – in a gleaming white tunic with breeches to match. At this stage, she’s already beaten her scheduled opponents on the women’s side. In a few moments, she’ll take on the army Sergeant managing the competition – and beat him as well. And did so in fancy breeches. Because this isn’t just any fencer. She’s a champion swordswoman. She would later become leader of an all-women’s ambulance squad in WWI. And she would be at the heart of a 1920s lesbian book scandal. This is…Toupie Lowther.

At this stage, Toupie Lowther is only 24 and she not messing around. Her name is one she adopted really early on, instead of her birth name, May – so that’s the one we’ll go with. In French, this is the name for a spinning top – twirling incessantly, perfectly balanced, till it eventually, inevitably, runs out of steam. And I don’t think Toupie could have found a better name for herself if she tried – spinning from a science degree at the Sorbonne to the world of sports with drive, passion and an unpredictable streak. Toupie would have been well known for her tennis playing as well – and reports of her playing maybe give some insight into who she was as a person as well. “Brilliant, but erratic.” Toupie soon rose to become a skilled tennis player who evolved from amateur’s women’s tennis matches to facing contenders across Europe as well as British tournaments with fanciful names. The only one I knew was Wimbledon, if I’ll be honest. Toupie is committed – and competitive. But the passion that perhaps contributed to her success in the first place – also led to some major flaws. Here is an excerpt from Forty Years of First Class Tennis published in the 1920s by George Hillyard which probably isn’t a page turner for non-tennis players but also does give us some insight into her personality: “Here is the extraordinary case of a player whose potentialities were greater than any other English lady who ever walked onto a court, but who, unfortunately was saddled with a temperament which was so hopelessly unsuitable to lawn tennis that it reduced her play…” This feels like polite tennis playing language for “she broke her tennis racket at the end of every match out of sheer rage.” Well hey – don’t worry about Toupie too much because there’s a second sport she excelled at which perhaps not only suited her hot-headedness but made her thrive. And this, you guessed it, was fencing. A short fun recap on women’s fencing in the 19th century. The earliest records we have of fencing manuals show women in them, as early as 14th century Europe. And women picked up swords for battle or for casual civilian bloodshed even earlier than that. So the idea of a lack of organised women’s fencing in a sports capacity before the 19th century doesn’t mean it didn’t exist beforehand and certainly not that women were not capable of fencing nor willing to learn – more that records were lacking and that there was more widespread lack of access for many women. That access widened somewhat in the 19th century. More or less. It would have been easier for upper-class women like Toupie to take part in the sport – as early as the age of 15 in her case. Ten years later, we have records of her refereeing a women’s fencing match at MacPhersons Gymnasium on Sloane Street in London – the very place she learnt to take up arms – at a time in which women’s fencing clubs would be more popularised. But while men’s fencing was admitted at the Olympic Games from 1896 women had to wait till 1924! Which sucks. But did not prevent them from organising their own matches and adding a layer of competition to a sport which was often seen fit for women, as an upper-class passtime destined for fitness and elegance rather than, you know, learning how to hit people with swords. You guessed it, the people spouting this condescending stuff were men. It was seen as a “noble” art for girls from “well to do” families and the public exhibition of women fencers in Europe definitely blended in with a form of entertainment for audiences at the time. Not that one interest in entertainment and elegance could not align with the other in terms of sport skills. For example Johann Hartl’s women’s fencing class, founded in 1873, aimed to train dancers and actresses in the proper use of weaponry as props in fight choreographies. They developed such an interest and skill that the group ended up touring across Europe and the US doing fencing demonstrations! Reading the press of the end of the 19th century reveals a kind of amused, again very condescending fascination with the idea of women fencing and the sense it could be tolerated if it stayed within the confines of a certain status quo. A 1885 review of a demonstration that this Viennese women’s fencing group did in Paris notes they have different colour uniforms which are both “elegant and chaste” with a light skirt. And also spends way too much time talking about how exciting it is when their skirts lift up because this is the 19th century and men are overwhelmed with the idea of a bit of leg showing. A lot of 19th century imagery actually shows fencing women in various elegant fencing outfits – when they’re not directly shown in more sexualised, pin-up poses. The language is coy, either seeing fencing as a leisurely passtime rather than a real sporting career for women or viewing any fencing woman as dominated by her passion, trying to fulfill or replace men in some way by taking up arms. Leading to more then a few homoerotic postcards of women prodding each other wiith swords. Or pictures of a threatening sword wielding woman who might kick men’s butts. My favourite is a 1905 postcard that shows a woman fencer with the caption “just you try and break up with her now!”. It’s weird infantilizing, language that under the guise of jokes, sees women taking up what is seen as a traditionally masculine activity as a threat if things are taken into competitive territory beyond the realm of beauty and fitness. And most of all, it was seen as the latest fashion in its popularity – not the start of a women’s sport in its own right, as this article from 1897 insists regarding the lady who fences: “(…) Whatever fencing may be to her in the future, today it is simply a fad of the hour. Undoubtedly it will add to her strength, give her more grace, make her even more beautiful and winning than she is, but with all that it cannot make a man of her.”

So when Toupie overhears fencing master Captain Alfred Hutton make a condescending comment along the same lines about the ability of women fencers, she’s like “say that again to my face” She challenges him to a duel. At this stage, she’d quickly risen to prominence, been named the champion fencer of the UK and if she could beat women opponents, she could also beat male twerps who thought a woman could never lay a finger on them. Toupie says – screw your status quo. I can fight as well as men. In fact, any woman can. And they can wear practical clothing while doing so as well! Up to this point, women fencers would have worn either skirts or bloomers. Which in itself is perfectly doable. I mean, I draw women fencing comfortably in skirts – a lot. I’m a huge advocate of full-on duelling in ballgowns. And the skirts worn would have been cut more like cycling skirts meant for sports in the first place. Bloomers which I can only describe as fantastically poofy pants, are also great as an alternative to big heavy skirts and have an awesome feminist history behind them. But just like skirts with pockets big enough to fit a phone or options for every body type, it’s nice to have options. And Toupie Lowther was like – I want that. I want options. Enter the breeches, like male fencers at the time – essentially trousers that stopped at the knee, held up by suspenders and allowing for some serious leg in knee-high socks action. It’s a look. And it’s a GOOD look. Toupie wasn’t the first woman to wear breeches in fencing – other women fencers like Lady Colin Campbell would adopt the outfit – with black silk breeches, a silk shirt and a narrow corset belt with a soft grey or black jacket, black stockings and silver buckled shoes. That is very stylish.

Which brings us back to that Gymnasium in Aldershot. Toupie knows the rules around men and women in sports and in society alike are unfair – and she’s intent on breaking them. And she’ll do so while being her own brash, headstrong self. We do not know how Toupie presented herself to the world outside of sports by the turn of the century when we see her in a newspaper article from 1900, posing proudly and defiantly in her breeches, foil blade at the ready as if to say – oh, you don’t like this? Well, beat me first. Then we’ll talk. But what we do know is that she would later on find her lesbian community in which her trouser-wearing would blend into her everyday life. It’s possible that even then she was experimenting with what she could and could not get away with. And how she could embrace a more masculine appearance as a lesbian, gender non-conforming woman in life and in sports alike. And Toupie makes a difference. She’s interviewed and talked about a lot at the time. She’s admired by her peers. She’s showing fencing women’s value and skill. But we can imagine, this whole situation feels frustrating to a woman who knows she can’t officially aspire to be on the same sports level as men as they go on to compete in the Olympics and she’s left behind in Aldershot. Maybe it ended up being too much, despite the trail she blazed.

Because by the time women fencers’ had the right to compete in the Olympics 1924 she had retired from the sport more than a decade before. The barriers she faced and aimed to destroy and her outspokenness about taking on men could have prompted her to take part in the Suffragette movement. And there are some allegations she did so. Unfortunately – we have no way to confirm or deny this. Only a single link – the fact that she, like many Suffragettes, was a practitioner of jiu jitsu. Because – of course she was. Jiu Jitsu instructor Edith Margaret Garrud, one of the first martial arts women instructors in Europe at the time practicing jiu jitsu alongside her husband, started a self-defense club from 1908 onwards for the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) – a women-only organisation that would become known as the Suffragettes. The WSPU’s fight for women’s suffrage extended from 1903 to 1918 and their protests included civil disobedience and direct action at public events, vandalism and arson. During that period many imprisoned women went on hunger strikes as protest and were subject to horrible treatment including force-feeding, as well as intense violence and harassment by the police during these arrests. In 1913, the Cat and Mouse Act meant that Suffragettes on hunger strikes were no longer force-fed. Instead they were left on strike till they were very weak, then legally released, left outside of jail for a period long enough for them to recover – and then re-arrested on the same charge they had originally been arrested for. The WSPU was like, oh wow. Wrong move. We’re gonna make you regret that. They form a protection unit of thirty women called “The Bodyguard” – also known as the Jiujitsuffragettes and, obviously, my favourite nicknames, The Amazons. Their role is to protect suffragettes who have been released to prevent re-arrest. Edith not only teaches them ju-jitsu to do so but also trains them to use weapons such as Indian clubs. She conducted secret lessons and the Unit engaged in combat with the police in events such as the “Raid on Buckingham Palace” in May 1914. And the media coined the term – suffrajitsu. Was Toupie part of this crew? Like I said – no proof. Most of what I have seen is completely unsourced, which, as all historians know, will get you banished from the guild of serious historians. But there’s a silver lining. She benefited from a Suffragette fictional reinterpretation as a member of the cast of characters in the graphic novel Suffrajitsu by Tony Wolf. In which she is none other than the leader of the Bodyguard unit. It’s obviously not historically accurate but an interesting look into Lowther’s fictional reinterpretation. Lowther does not need to be part of the Suffragettes to be an interesting figure in her own right. But this cultural legacy and how she ended up in this comic book is an interesting link with ju-jitsu and the Suffragettes. And what comes next is an interesting link to the events of World War I since, after war breaks out, the Bodyguard unit is disbanded. This is because the leader of the Suffragettes, Emmeline Pankhurst, had suspended militant Suffragette acts and mobilised the WSPU in favour of the war effort. This translated into Pankhurst’s involvement in the white feather movement, giving feathers to men who would not enlist for war. A sign of what Pankhurst saw as cowardice rather than a refusal or inability to take part in a war that would kill so many soldiers and injure and traumatize many others. So let’s remember this just as we remember the Suffragettes – just as we should remember how they excluded women of colour from the movement and attempted to suppress the lesbian and bisexual women at its core. Amongst them none other than Emmeline Pankhurst’s own daughter Cristabel.

So many people had a lot of valid reasons to avoid taking part in the war – like, you know – it’s a war and they don’t want to kill people. Or die? But Toupie wanted to take part. And she wanted to be on the frontlines. In spite of women not – technically – being able to enroll as soldiers. Not that this prevented many women who were able to find a way around the rule. Like Flora Sandes, a British woman who was an officer of the Royal Serbian Army, after initially starting out as an ambulance volunteer deployed in Serbia. On the French side, Marie Marvingt dressed as a man to fight on the front, was involved in flying combat missions and was a nurse. And prototyped the first air ambulance just to round things off. We also have accounts of Maria Leontievna Bochkareva, a Russian soldier who led her own battalion of women soldiers called the Women’s Battalion of Death. Which, sure, existed as a propaganda tool to shame men into taking part in war because “if a woman can fight, so could they.”

But, condescending comments aside which seem linked to whatever women tried to do at the time, they were still doing the thing. And let’s not forget that these are only the records we have – that many women may have fought – and died – dressed as men at the front without having their accomplishments documented. But in the wider context of the frontlines, while women could not always openly fight in the literal sense they are nonetheless definitely involved in conflict. And the women I just mentioned give you a clue in the variety of roles they took on – as soldiers, but often also as medical units. These would be close to the front – often in dangerous, life threatening conditions. And many would involve volunteers in their ambulance units who would have been considered “unfit” for fighting – too young, too old, wrong gender. Though often these units composed of women were relegated to support work compared to men’s ambulance units on the frontlines.

And Toupie knows this. Her gameplan isn’t to translate her sword fighting skills to fighting on the battlefield. But nor is it to serve as a nurse. Her aim? To look at the bigger picture. To form an all-women’s ambulance unit that could be on the frontlines of the battlefield, exactly on the same terms as men’s ambulances. It’s 1917. Toupie sends a petition with that very request to the French Army. And she formulates this plan carefully – not by herself but with a co-conspirator who also has an insider perspective. This is Norah Desmond Hackett, who at this stage is the director of the Women’s Emergency Corps affiliated with the French Army. The proposal of the unit that she puts forward in collaboration with Toupie is that the unit will be dual purpose. Toupie will lead a group of ambulance drivers, providing their own set of cars. And Norah would provide what she had provided up to now with her war service – a Canteen section. The fact she’d already been providing essential work with the military decoration of the Croix de Guerre for her troubles no doubt led to the proposal being successful.

Toupie now had a mission – recruit not only a fleet of cars – but women who could drive them. And the donations and offers to volunteer started rolling in. No doubt helped by Toupie’s upper-class connections – owning a car in the early 1900s was not cheap. But also no doubt helped by her own connection to a whole range of women who, like herself, were interested in traditionally “masculine” hobbies as they were perceived at the time. Like driving cars and being able to repair them. Toupie had been tinkering with cars for a while as a driver and mechanic. And that was the prerequisite for this mission. Alongside a lack of direct attachment to any domestic duties that may have prevented them from going to war in the first place. Or the ability to say screw it to those duties, drop everything and go drive some cars in a warzone.

And we’re now in January 1918 in France, months after this first pledge. A low rumble and roar sounds across the French countryside. Norah Desmond Hackett, at first sunlight, looks to the east. It’s a fleetload of cars – different cars, different sizes but all branded with a red ambulance service cross. A lot of cars. 22 to be precise – with 30 women drivers either behind or beside the wheel. And among them, leading the charge – Toupie Lowther. Out of the range of women she had recruited, only a few had the title of “Mrs”. Most were unmarried. And many found a sense of community in their driving and tinkering with engines alongside fellow enthusiasts. All this aside, there were rumours of many women in the unit not only fighting together – but flirting together. In short – there were a fair few women loving women driving alongside our leading lesbian. I’m not saying it was a lesbian power unit. But…you know what, it’s my podcast, so I can do whatever I want. Lesbian power unit.

Rumoured sapphic shenanigans aside, not much is known about the women who accompany Toupie, or their personal lives or aspirations. Some remaining photographs show them posing alongside one of the ambulances, in army uniform – in their case a long trench coat and skirt which would have protected them from the elements and been practical enough to deal with the hard labour of hauling bodies into ambulances, repairing motors on the go and driving in the worst conditions you could possibly imagine. These women look tough and badass and strong. But some pictures show their softer side. One picture shows one of them smiling, posing with a small mascot, an adorable little kitten. The story doesn’t say if said kitten accompanied them on their missions. But I kind of hope it didn’t. When Toupie arrives metaphorical guns a blazing with her lesbian power unit, Toupie and Norah are made lieutenants, attached to an army unit and said lesbian power unit is sent to Creil. This is not the frontline but it is still in an active war zone. This is their baptism of fire. Any woman who can’t manage the stress of engines breaking down while hauling in the wounded and driving at break-neck speed to the closest army hospital…is soon sent home. And what remains isn’t a gang of bored rich lesbians looking for a bit of excitement. It’s a well-oiled machine, putting in the work. And proving any sexist nay-sayers wrong.

But this prompts Toupie and the others to point out this is not the front they were promised – where they can do more if not most of the life-saving work. So Toupie does what Toupie does best – she challenges the men to call them out on their own sexist bullshit. She goes all the way to the top and drives 50 miles to meet the man in charge of the French military transportation service, confronting him in a meeting with 50 other men on his side. The Commandant is very transparent about why they are not at the front. He doesn’t want blood on his hands. More specifically he does not want a bunch of women’s blood on his hands, especially if most of them are from the United Kingdom. He’s thinking about the diplomatic paperwork with a seasong of sexist doubt. But Toupie badgers him – and won’t give up. At his wits’ end, he asked: “Am I to send you to your possible death?” To which Toupie responds, dryly: “I am of the opinion that a few women less in the world is of no importance.” Bold move. And an efficient one apparently because a few weeks later they are deployed to Compiegne, at the front, as a unit at the heart of the battlefield.

The opening lines of her statement to the Times in 1919, reporting this experience, is the last way anyone would describe World War I: “It was a wonderful time (…) we were often 350 yards from the German lines awaiting the wounded, under camouflage.” But less than a year later, Toupie Lowther’s report to the Imperial War Museum on the creation of the ambulance unit reveals something else between the lines of the alleged wonderful time. She describes what the plan had always been: “to drive an ambulance under bombardment and shell fire…[undergo] the hardships which field ambulance drivers doing front line work have to undergo.”

And here, the lines blur in terms of what it meant to be fighting, on the battlefield. Toupie and her women were fighting to save countless lives – and by all accounts, they succeeded. They carried thousands of soldiers across. And their willingness to be at the heart of the action and drive in war territory in the worst conditions you can imagine made a difference. The unit proved its point – and its value. Any skepticism from higher ups about their womanhood and the risk they would cause a diplomatic mess if they were killed was dispelled. Women could take part in the fight. And that proof was only reinforced with Compiegne being the place in which the unit – and Toupie – received the military honour of the Croix de Guerre. After more than a year and a half in action Toupie’s unit was disbanded in August 1919, prompting her return to the UK. But little did she know that her WWI exploits during that one year and a half would live on in another way. And live on in lesbian legend.

So we’re in the 20s in London. And let’s gate crash…a fancy dress party! Because why not. This is the roaring Twenties and people are partying. And we have seen Toupie in the thick of WWI and the fencing circuit – but now we find her as the host of said costume party. Presumably living her best life – surrounded by lesbians. Never short of gossip – and never short of drama. It would be hard to summarize the social scene for wealthy, usually mainly upper-class lesbians in Paris and London in the 1920s, filled with decadent parties and a lot of writing about one another and painting one another. But Toupie was definitely part of it – using her status and wealth to launch fancy dress balls for her lesbian friends. A popular staple of upper-class lesbian life in the interwar seems to be the salon, which Parisian lesbian and poet Nathalie Barney was an expert in given she hosted one for about 60 years. So what is a salon? Usually a weekly event in which people could discuss literature, philosophy, art, poetry and authors were hosted. Not to be mistaken with saloon, though admittedly a lesbian saloon in the Wild West does sound amazing. It became a way for lesbians to be able to socialize and meet. So apparently, Toupie ran her own lesbian salon in the 1920s in London, where she would have met and socialised with a range of fellow lesbians. Amongst them Radclyffe Hall and her girlfriend, Lady Una Troubridge. After all, they were close friends with Toupie since they met in 1920. And when you thought about rich lesbian eccentrics, those two probably came to mind. Radclyffe Hall was an English poet and writer. She would became most known for lesbian novel The Well of Loneliness.

But by the time she met Toupie, that book was not yet written. Because it plays a key part in our story. And Una? A British sculptor and translator. The couple raised dachshunds together as well as griffons – the dog, not the mythological creature. Most paintings or photographs of them will have them looking dapper as heck holding dogs. They’re by no means perfect – we can find them stylish now but they’re also the product of a privileged, upper class elite and Hall had anti-Semitic and facist leanings. But they are an important part of the life of interwar lesbian London. And would play a messy, complicated part in Toupie’s own life. In that circle we also find Nathalie Barney – American playwright, poet and novelist who was mainly known for her pretty banging Parisian lesbian salons which attracted a lot of modernist artists. Her poetry is very explicit about her love of women and she embraced that to the fullest – she was also polyamorous although not really with her partners’ full agreement which is a bit messy and complicated. Yep these lesbians are all a mess. What has changed? Well, at this party one of Nathalie’s longest relationships may have been there. This would be the American painter Romaine Brooks, who would have coincidentally painted a famous portrait of a frontline nurse during WWI – La Croisée. This heroic, stark figure would have aligned with what Toupie would have experienced – and showed another side of wartime many of these women would have experienced first hand as volunteers. It expressed a new interwar aesthetic – the modern woman. The modern woman had either taken on traditionally male-dominated jobs during the war or benefited from more freedom and agency in general. Women started to reclaim masculine wear, especially the uniform-like aesthetic of service jobs in which women had served, to reclaim public space. And this feminist aspiration ultimately intersected with lesbian aspirations too. Masculine wear and specific codes like short hair, smoking and wearing a monocle became a way, at least for upper-class lesbians, to recognise one another and slowly form more of a community in terms of public spaces and nightlife. And Toupie was a part of it – in the parties she threw and the clothes she wore.

It’s hard to know if Toupie took up fencing again and once more donned white breeches. But either way, she would have cut a striking figure at the time in terms of adopting a more masculine fashion and gender expression which corresponded to the experiences of many of her fellow lesbians, many of which used male nicknames for each other as well as male pronouns. For example, “John” is commonly used to refer to Radclyffe Hall as a term of affection and intimacy by Una. And Toupie was no exception. In fact, Radclyffe and Una have a specific nickname for her, relating to this idea of a lesbian community who found themselves through this identification with masculine codes – “Brother”. In early 20th century lesbian circles this would have been common. There is an ongoing tradition of lesbians using male pronouns and male nicknames. They would have gendered themselves as and write about themselves as women but their gender expression and identity as lesbians would also have embraced masculine gender expression. What is clear is that early 20th understandings of what it meant to be a lesbian is that this was conflated in varying degrees with gender expression and even identity. The very general idea being that it was believed that attraction to the same gender, as a woman, was linked to possessing masculine traits. As such, many queer women around this period who were able to found identification and comfort around reclaimining masculine fashion, activities and even behaviour.

This said we absolutely need to account for the fact that many of these figures could very well have been experimenting with trans identity, without having the language or concept to express what they were feeling. Lesbian histories, trans men and non-binary people’s histories are often very closely linked as it is sometimes near impossible to guess how many of these figures would have identified today. By way of example, there are also cases in which a person’s desire to not be gendered as feminine or masculine in any cases is completely clear-cut and documented as a part of what we would now call their trans identity. The artist Gluck, for example, chose this name and was very clear about having “no suffix and no prefix”. So gendering Gluck in gender-neutral terms, not using Gluck’s rejected birth name or avoiding pronouns altogether makes sense. Gluck would have been part of these queer circles and part of this lesbian culture but resisted being gendered. We don’t know how early on Toupie adopte trousers in everyday wear, but one thing’s for sure. Once she did, she went all out. Una was so struck by Toupie wearing a pair of stunning black silk trousers it justified an entry in her diary. I can imagine that a sleek suit and trouser combo was probably what she was wearing when she strolled up to her girlfriend of the time and said – Hey – what to go on a date? Let’s go on a motorcycle ride across the Alps. Because Toupie also happened to be the first woman to ever ride a motorcycle. And, considering the first motorcycle was invented in 1885 – probably also loved the idea of living a bit more dangerously. In her own accounts, Toupie sets off across the Alps, girlfriend perched on behind her, probably holding on for dear life.

This is Fabienne Lafargue De-Avilla – a French and British writer who probably throughout the Alps motorcycling was a great romantic idea at the time and wasn’t sure now as the damn machine sputtered and stuttered across winding roads. The journey had some bumps – and some of them were far beyond Toupie’s control as a driver. So she gets arrested at the Franco-Italian border for “dressing as a man.” Toupie things – first, screw you but second – fine, I’ll wear a skirt on the way back. On the way back, she’s arrested while she’s wearing a skirt – this time for “dressing as a woman.” This gender confusion and misgendering mingled with transphobic assumptions around what a woman is “supposed” to look like, both reviled for being too gender conforming then for not being feminine enough would have been part of what Toupie would have faced at the time – something she could not escape, neither in London nor in the far reaches of the Alps. At this stage – Radclyffe Hall, Una Troubridge and Toupie Lowther spend a lot of time together. Una’s diaries recount evenings with Toupie and Fabienne and frequent visits to Paris. And here’s where it gets interesting. Radcliffe Hall draws from many different experiences and aspects of her life and the people within it to write. So when Hall’s 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness is released, many would have recognised some fragments of a certain friend’s own life in the main character Stephen – a gender non-conforming lesbian who was a fencer and accomplished sportswoman (whose interests include jiu jitsu, tennis playing and driving) and ended up leaving her comfortable upper-class life to lead an all-women’s ambulance unit on the Front during WWI, becoming a war hero. So…yes. A few similarities. When I first picked up the book, it was in the used books section of the Shakespeare & Company bookstore in Paris. And the quote on the back struck me (and of course immediately justified buying it). “I would rather give a healthy boy or a healthy girl a phial of prussic acid than this novel.” Which in so many ways so nicely encapsulates the mindset homophobes and transphobes still hold today. You’d rather kill a child than give them a book that could help them explore their feelings or just be more open to love or gender that are different from their own experience? Okay. That’s healthy. And that’s coming from the same people who enjoy saying “Will someone please think about the children?” The author of this charming quote is James Douglas and he launches a campaign against the novel deeming it perverse because you know, it has two ladies kissing once, and a mention that one night they were “not divided.” Well, one thing that WAS divided was opinion – since on the one hand, the outrage shut down publication of the book in the UK and on the other all this bad publicity fuelled demand for it in its clandestine printing in France as well as support from media and other authors in terms of freedom of expression. Copies arriving from France were seized, then released by Customs because the Chair of Customs read the book and was like “dudes, this book is fine”, released the books which were then seized again by the police, and led to a range of legal battles for the publisher. It was a mess. Which is why we’re now at court- for specifically the obscenity trial for the book in 1928.

Now we don’t know whether Toupie was there. In fact it’s likelier she was not. But if she wasn’t in person, her spirit and her presence as a source of inspiration hung heavily over the trial. Because the trial against the book included the accusing party pinpointing direct mentions of the ambulance unit’s ambient lesbianism in the book inspired by the real-life ambulance unit – saying that in the unit there was “many a one who was ever as Stephen.” Something that Hall would also have witnessed. Una recounts in her diary who Hall had commented on “the perpetual sexual carrying on between members of the same Army Unit” referring to Toupie’s friends, presumably at her salon once their wartime adventures were behind them. This was seen as offensive by the Chief Magistrate Sir Chartres Biron who was ultimately the person who had the power to rule out the book as obscene, because the same unit had obviously been hailed as you know…heroes. Quote from the trial: “This takes place at the Front where, according to the writer of this book, a number of women of position and admirable character, who were engaged in driving ambulances in the course of the war, were addicted to this vice.” This guy’s brain was imploding. How could you possibly imply that the very same women who had saved lives on the frontlines were also decadent lesbians going to hell? The mind is truly boggled. Boggled, I tell you. Hall was outraged and would later comment: “I had written of them as I believed to have been, pure living, courageous, self sacrificing women facing death day and night in service of the wounded.” Of course, we can appreciate that according to Una, Hall isn’t exactly as reverent and kind when she talks about Toupie’s friends previously.

The final verdict of the trial? Obscenity. And with it, the destruction of any copies on UK territory. And what did Toupie think of all this? There are some allusions to her distancing herself from her usually gender non conforming style by wearing feminine fashion after the trial, perhaps to dispel suspicion around what would have been quite a public connection between the lesbian WWI all-women’s-ambulance-unit leading, Croix de Guerre wielding protagonist and herself. A reminder that for all of her ability to live more or less openly as a lesbian to some extent, a UK-wide trial would have caused immense damange to her at a time in which lesbians were seen as unnatural and immoral. But over time, what seems to have happened is that Toupie fully embraced the portrayal and fully claimed her role as the inspiration for Stephen, which is what perhaps, paradoxically, soured her friendship with Radclyffe Hall. Which is confusing. Toupie would already have had access to extracts from the short story Miss Ogilvy Finds Herself which later on inspired The Well of Loneliness which she also would have known about. It seems pretty obvious that the character of Stephen with her weightlifting and fencing prowess alongside her, quite literal management of an all-women’s ambulance unit during the First World War in France, would have been inspired by Toupie. Diana Souhami, in the Trials of Radclyffe Hall, also indicates how clearly The Well of Loneliness was inspired by a range of very real people in Hall’s life, sometimes in ways that were blatantly obvious and would have been instantly recognisable to anyone in the know. And yet Hall claims that it was all fictional in her author note and Una writes first of Toupie’s resentment and then later on that she had “acquired the illusion that she had served as a model for Stephen Gordon.” So…the end of this friendship is messy, needlessly dramatic and a bit confusing. Una doesn’t seem to like Toupie a lot. And so in true lesbian drama fashion – some finer details are lost to history.

I would like to say that the end of Toupie’s life’s a happy one, and that she is symbolically married to Fabienne and that they live happily ever after…But this is real life so instead things are super grim. According to Una, she suffered from tuberculosis and alcoholism, saying that “At night she railed at God from her window for taking her wife Fabienne Lafargue De-Avilla from her.” In the same accounts, Una describes Fabienne as promiscuous, and cruel, living in a cottage nearby that Toupie owned with her lover Liza. Una speculates that Fabienne awaits Toupie’s death so she can get her money and refuses Toupie’s invitation to stay with her. Whatever the truth, Fabienne was in Toupie’s will – as her god-daughter, probably the only way she could have left her anything, outside of the legal marriage they would not have been allowed to have. Either way, Toupie lived the rest of her life in the village of Pulborough in West Sussex in South-East England until her death in 1944. But she decides to go out in a…strange and unconventional way. She requested her body to be laid out for four days. After which time, if doctors confirmed she was indeed dead, they should cut her jugular vein, cremate her and scatter the ashes to be swept up by the wind. Doing it her way – till the very end.

This story has it all. Fencing! An all women’s ambulance unit! Lesbian gossip! Gender non-conforming fashion! But what I have really appreciated is getting out of the comfort zone in terms of my own assumptions about what it means to look at women with swords in military history. Toupie, a fencer, did not use her sword on the battlefield. In fact she did not kill a single person – that I know of. And many people would argue with me about both her classification as a swordswoman and as a warrior woman – given she never took up a sword to specifically fight or duel outside of a sports context nor was part of fighting military personnel. But just like Toupie challenged what she was or wasn’t allowed to do – let’s also challenge who is or isn’t considered a military figure. What this story shows, like so many others, is that so many women may have attempted to help – and failed, due to lack of access, resources or credibility. And those who succeed in a traditionally male environment are often touted as exceptions to their gender, different from any other woman out there. But Toupie’s ambulance idea would not have succeeded out of sheer determined will. (Nor entirely out of her privilege as a white upper-class woman though let’s face it – that was definitely part of it). She had help from a woman on the inside and built up a network around her. Toupie had been able to tap into a network of women who could be actively involved in the fray – and may have also felt what she felt. Powerlessness. Frustration. The feeling they could take part and fight in their own way. And that together they could prove what they could do – and save the lives of the many men who would have mocked and doubted them in doing so.

Thank you very much for listening. I hope you’ve enjoyed this episode researched, narrated and produced by me, Claire Mead. You can find all the sources and recommended reading for this episode in the show notes at clairemead.com/bustlesandbroadswords. The music is “Captivated by Her” by Cody Martin. You can find all episodes of Bustles and Broadswords anywhere you listen to podcasts. You can follow me on Twitter on @bustleswordpod on Twitter to never miss an update or you can follow me at @carmineclaire for general info and rambling on women with swords and LGBTQ+ histories. Stay safe there sword lady lovers and see you in a future episode.

Show Notes

On the piste with Toupie, after an original publication of this in 2021! I loved researching this episode but it did present a few challenges so specific to trying to research women and particularly lesbian and bi women’s histories.

A number of accounts of Lowther’s life either make mistakes in confusing her identity with other members of her family, which result in Lowther ending up with a husband and son due to confusing her with a Lady Barbara Lowther. Fabienne as Toupie is often presented as her goddaughter when a number of sources confirm they were first and foremost lovers. It seems intriguing to want to erase what was central to Toupie’s life in favour of a narrative that either hides her life or invents a husband and son for her. This is strange but hardly surprising: the histories of historical lesbians are often erased and their relationships shown as friendship or sisterly love. While Fabienne was Toupie’s goddaughter it is pretty clearly established that Fabienne was also a lesbian and that they were lovers. The fact that Toupie mentions Fabienne as her goddaughter in her will rather than her “wife” is…hardly surprising, given that there would have been no legal way to establish her as a legal beneficiary in any other way.

My stance has been to prefer sources that have given a fuller picture and more researched account of the way Toupie lived her life from a feminist and LGBTQI perspective.

Sources and Recommended Reading:

Jack Halberstam, Female Masculinity, 1998

Diana Souhami, The Trials of Radcliffe Hall, 1998

Emily Hamer, Britannia’s Glory: A History of Twentieth Century Lesbians, 1996

Katrina Rolley, Cutting a Dash: The Dress of Radclyffe Hall and Una Troubridge

Laura Doan, Passing Fashions: Reading Female Masculinities in the 1920s

Fencing for Ladies 1901 newspaper article

The Imperial War Museum’s Toupie Lowther timeline

The Times August 5, 1919 – Englishwomen with the French army

Medal card of Lowther, Toupie Corps: French Red Cross Rank: Driver, National Archives

Lady fencers – transcript of an article in the harmsworth magazine, issue july 1899

Leave a comment